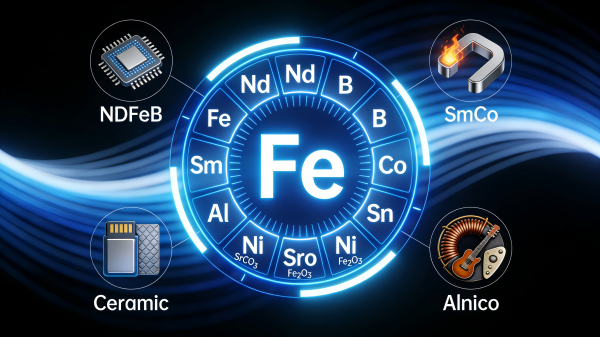

Modern permanent magnets aren’t made from pure elements. They’re engineered alloys. The specific mix of elements determines how strong a magnet is, how much heat it can handle, and how much it costs. To answer what elements are in magnets, we need to look at the unique recipes for each type.

The main elements include Iron (Fe), Neodymium (Nd), Boron (B), Cobalt (Co), Samarium (Sm), Aluminum (Al), Nickel (Ni), and ceramic compounds like Strontium Carbonate. This guide breaks down the composition of the major magnet families. We’ll explain how these elements create different properties and help you choose the right material for any use—from industrial purchasing to scientific research.

Here’s a quick look at what’s inside each major magnet type:

- Rare Earth Magnets: Neodymium (Nd), Iron (Fe), Boron (B); or Samarium (Sm), Cobalt (Co).

- Alnico Magnets: Aluminum (Al), Nickel (Ni), Cobalt (Co), Iron (Fe).

- Ceramic (Ferrite) Magnets: Iron Oxide (Fe₂O₃), Strontium Carbonate (SrCO₃).

Table of Contents

Four Main Magnet Types

Understanding magnet composition means breaking down the four main types of permanent magnets. Each type has a different mix of elements that creates its unique performance profile and best uses. This knowledge is essential for engineers making purchasing decisions and students studying material science.

Neodymium (NdFeB) Magnets

Neodymium magnets are the strongest magnets available today. They’re made primarily from Neodymium (Nd), a rare earth element, combined with Iron (Fe) and Boron (B).

This alloy is often called by its chemical formula: NdFeB.

Small amounts of other elements are often added too. Dysprosium (Dy) and Praseodymium (Pr) can be mixed in to improve how the magnet performs at high temperatures.

These magnets are incredibly strong. Their strength is measured as Maximum Energy Product (BHmax). They offer the best strength-to-size ratio you can get.

However, they have moderate temperature resistance. The high iron content also makes them rust easily. This means they almost always need a protective coating.

These properties make them perfect for high-performance uses. You’ll find them in electric car motors, high-quality audio equipment like headphones and speakers, computer hard drives, and powerful magnetic separators.

The exact ratio of elements determines the magnet’s grade—like N35, N42, or N52. Higher numbers mean stronger magnetic fields. For applications that need maximum force, our range of sintered Neodymium magnets offers industry-leading performance.

Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) Magnets

Samarium Cobalt magnets excel in high-temperature environments. They were the first commercially successful rare earth magnets.

They’re made mainly from Samarium (Sm), another rare earth element, and Cobalt (Co).

This combination creates a magnet with high strength—second only to NdFeB magnets. More importantly, SmCo magnets handle extreme heat exceptionally well and resist corrosion better than other types.

They don’t need a coating. This is a big advantage in sensitive or sterile environments.

Their toughness makes them essential for military and aerospace applications, critical medical devices, high-temperature motors, and sensors that must work reliably under extreme heat.

There are two main SmCo magnet series. The SmCo5 series typically works up to 250°C. The Sm2Co17 series, with more cobalt, can withstand temperatures up to 350°C. The development of SmCo magnets was a major breakthrough, extensively studied by institutions like the Materials Research Society (MRS).

Ceramic (Ferrite) Magnets

Ceramic magnets, also called ferrite magnets, are the industry workhorses. They’re the most widely used magnets because they’re affordable and offer balanced performance.

Unlike metal alloys, they’re made from ceramic material. This is created by heating a mixture of Iron Oxide (Fe₂O₃) and either Strontium Carbonate (SrCO₃) or Barium Carbonate (BaCO₃).

Strontium ferrite is most common today because it has better magnetic properties.

Ferrite magnets offer moderate magnetic strength but resist corrosion naturally. They’re hard and brittle but can operate at relatively high temperatures. They’re also difficult to demagnetize.

Their biggest advantage is very low cost. This makes them the go-to choice for high-volume, budget-conscious projects where extreme strength isn’t the main requirement.

You can find them everywhere: refrigerator magnets, small DC motors, budget speakers, and countless consumer and industrial products.

Alnico Magnets

Alnico magnets are the classic performers. They represent one of the earliest strong permanent magnet families.

Their name comes from their main elements: an alloy of Aluminum (Al), Nickel (Ni), Cobalt (Co), and Iron (Fe).

To improve their properties, manufacturers often add small amounts of Copper (Cu) and Titanium (Ti).

Alnico’s standout feature is incredible temperature stability. It can work in temperatures up to 500°C—the highest of any standard permanent magnet.

They also have high magnetic remanence (residual magnetism), but their coercivity is relatively low. This means they can be demagnetized more easily by external magnetic fields compared to rare earth or ceramic magnets.

Their unique properties make them ideal for specialized uses like electric guitar pickups, various sensors, high-temperature equipment, and legacy military systems. The stable fields they produce are based on the physics of electromagnetism explained by educational resources like HyperPhysics.

Magnet Material Comparison

There’s no single “best” magnet without context. The ideal material depends entirely on your specific needs. Required strength, operating temperature, environmental conditions, and budget all matter in the selection process.

We’ve created a direct comparison of the four main magnet types to simplify this complex decision. This table helps B2B buyers, engineers, and product designers quickly assess trade-offs and identify the most suitable material for their project. It moves from theoretical knowledge to practical application by comparing materials on the metrics that matter most for purchasing and design.

Feature | Neodymium (NdFeB) | Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) | Ceramic (Ferrite) | Alnico |

Key Elements | Nd, Fe, B | Sm, Co | Fe₂O₃, SrCO₃ | Al, Ni, Co, Fe |

Max. Energy (BHmax) | Very High | High | Low-Medium | Medium |

Max. Operating Temp. | Medium (~80-200°C) | High (~250-350°C) | High (~250°C) | Very High (~500°C) |

Corrosion Resistance | Poor (Requires Coating) | Excellent | Excellent | Good |

Relative Cost | High | Very High | Very Low | High |

Best For… | Max strength in small size | High heat & corrosion | Cost-sensitive applications | Extreme heat stability |

This table is a starting point. A neodymium magnet is the clear choice for applications needing maximum power in a compact space, like a drone motor. For a sensor inside a jet engine, the extreme heat and reliability needs would point toward Samarium Cobalt or Alnico. For a mass-produced children’s toy, the low cost and safety of a ferrite magnet are most important.

Why These Elements Work

The choice of elements for magnets isn’t random. It’s precise science rooted in quantum physics and material science. Understanding why specific elements create magnetism elevates knowledge from a simple list to deeper appreciation of the engineering involved.

The Role of Electron Spin

At the most basic level, magnetism comes from electron spin. Electrons behave like tiny spinning tops. This motion creates a minuscule magnetic field called a magnetic moment.

In most materials, electrons exist in pairs with opposite spins. This cancels out their magnetic fields.

However, certain elements—particularly transition metals like Iron (Fe), Nickel (Ni), and Cobalt (Co)—have unpaired electrons in their outer shells. These unpaired electrons have magnetic moments that don’t cancel out. This makes the atoms themselves tiny magnets. These are called ferromagnetic elements.

Crystal Structure and Domains

Having atoms with a net magnetic moment is just the first step. To create a powerful permanent magnet, these atomic magnets must all point in the same direction.

This is where crystal structure becomes critical. The elements aren’t just mixed together. They’re arranged in a specific, repeating three-dimensional pattern called a crystal lattice.

This lattice structure creates preferred directions for magnetization. It encourages the magnetic moments of neighboring atoms to align, forming large clusters called magnetic domains.

In an unmagnetized piece of material, these domains point in random directions. Their fields cancel each other out. During manufacturing, a powerful external magnetic field is applied. This forces these domains to align and creates one large, powerful permanent magnet.

The "Magic" of Rare Earths

This brings us to the “magic” of rare earth elements like Neodymium (Nd) and Samarium (Sm). While Iron is a strong magnetic building block, it can’t stay strongly magnetized on its own.

Rare earth elements have a unique electron structure. When combined with transition metals, they create exceptionally strong magnetic anisotropy. Anisotropy is the property of the crystal to “lock” magnetization in a specific direction.

This “locking” mechanism makes it very difficult for magnetic domains to become misaligned. The result is an incredibly strong and stable permanent magnet. This teamwork between Iron’s high magnetic moment and Neodymium’s strong anisotropy is what makes NdFeB magnets so powerful. For those interested in the fundamental elements, a high-quality Interactive Periodic Table like Ptable is an invaluable resource for exploring electron configurations.

Choosing the Right Magnet

With a clear understanding of different magnet compositions and their properties, the next step is a practical decision framework. This process translates technical data into real-world purchasing decisions and reduces the risk of choosing the wrong material.

When we help our clients select a magnet, we walk them through these key considerations. This ensures the final product meets all technical and commercial requirements.

- Define Your Required Strength (BHmax)

- The first question is always about power. Is maximum magnetic force in the smallest possible package essential for your design? If so, a Neodymium (NdFeB) magnet is the obvious choice. If moderate strength is sufficient and other factors like cost are more important, a Ceramic (Ferrite) magnet may be better.

- Assess the Operating Environment (Temperature)

- Where will the magnet be used? A magnet for consumer electronics will likely operate at room temperature. However, a magnet in an automotive sensor or industrial motor may face significant heat. Standard NdFeB magnets begin losing performance above 80°C. SmCo, Alnico, and certain Ferrites can operate at 250°C and beyond. Alnico is the champion of high-temperature applications.

- Consider Environmental Factors (Corrosion)

- Will the magnet be exposed to moisture, humidity, or other corrosive elements? Uncoated Neodymium magnets rust easily due to their high iron content. In damp environments, an inherently resistant material like Samarium Cobalt or Ferrite—or a properly coated NdFeB magnet—is necessary for long-term reliability.

- Analyze the Magnetic Circuit (Coercivity)

- Will the magnet exist near strong, opposing magnetic fields that could demagnetize it? Coercivity measures a magnet’s resistance to demagnetization. Alnico has relatively low coercivity, making it unsuitable for applications with strong repulsive forces. NdFeB, SmCo, and Ferrite magnets all have high coercivity and are much more stable in such environments.

- Determine Your Budget and Volume

- Finally, cost is a critical factor. Are you creating a low-cost, high-volume consumer product where every cent matters? Ceramic (Ferrite) magnets offer the lowest cost per unit of magnetic energy. Are you designing a mission-critical, high-performance component where performance justifies a higher price? SmCo and NdFeB magnets, with their complex processing and rare earth elements, carry a significant cost premium.

Navigating these trade-offs can be complex. For expert consultation tailored to your specific project, contact our engineering team for a custom solution. Magnet grades and standards are often defined by industry bodies like the Magnetics & Materials (M&M) Conference, which sets performance benchmarks.

Beyond Core Elements

The elements in the magnet are only part of the story. For many applications, especially those using high-performance materials, the elements on the magnet are just as critical for longevity and performance. These are the coatings and additives.

The main reason for coating a magnet is to protect it from corrosion. This is most important for Neodymium (NdFeB) magnets. Their high Iron concentration makes them as likely to rust as untreated steel. A coating acts as a barrier between the magnet and the environment.

There are several common coating elements and materials, each with its own benefits:

- Nickel-Copper-Nickel (Ni-Cu-Ni): This is the most common and cost-effective coating. It provides durable, corrosion-resistant protection and an attractive silver finish suitable for most indoor applications.

- Epoxy: A black epoxy coating offers excellent resistance to corrosion and various chemicals. It provides a slightly stronger barrier than Ni-Cu-Ni and is often used in outdoor or mildly corrosive environments.

- Zinc (Zn): Zinc provides a sacrificial layer of protection. It will corrode before the magnet material itself, offering good protection at low cost. It has a dull gray finish.

- Gold (Au): Gold plating is used for specialized applications. It offers superior corrosion resistance and is biocompatible, making it essential for many medical devices and sensors that contact the body.

Beyond coatings, additives play a vital role in fine-tuning a magnet’s properties. We briefly mentioned that Dysprosium (Dy) is added to NdFeB magnets. Its purpose isn’t to contribute to the primary magnetic field, but to dramatically increase the material’s coercivity and resistance to demagnetization at high temperatures. This allows NdFeB magnets to be used in more demanding, high-heat applications like electric vehicle motors. The science of preventing rust is a deep field, with foundational principles of electrochemistry and corrosion explaining why these coatings are so effective.

Conclusion

The elements in magnets are intentionally chosen and precisely combined to create materials with a specific balance of strength, temperature resistance, corrosion resistance, and cost. Understanding this magnet composition—from the rare earths in NdFeB to the iron oxide in Ferrites—is the first step toward successful engineering and procurement.

The answer to what elements are in magnets is not a single element, but a story of material science. It’s the story of how arranging atoms of Neodymium, Iron, and Boron creates unmatched power. It’s how baking Iron Oxide with Strontium Carbonate yields an affordable, reliable workhorse. Each type serves a purpose, driven by its unique elemental makeup.

Understanding this foundation is key to unlocking the potential of permanent magnets. Whether you’re designing a next-generation motor or sourcing a reliable component for your product line, choosing the right material is essential. For brands seeking a partner with deep material expertise and a commitment to quality, CNMMAGNET provides high-performance magnetic solutions tailored to your needs. Explore our capabilities and discover how we can empower your next project at https://aqmagnet.com/.

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

X